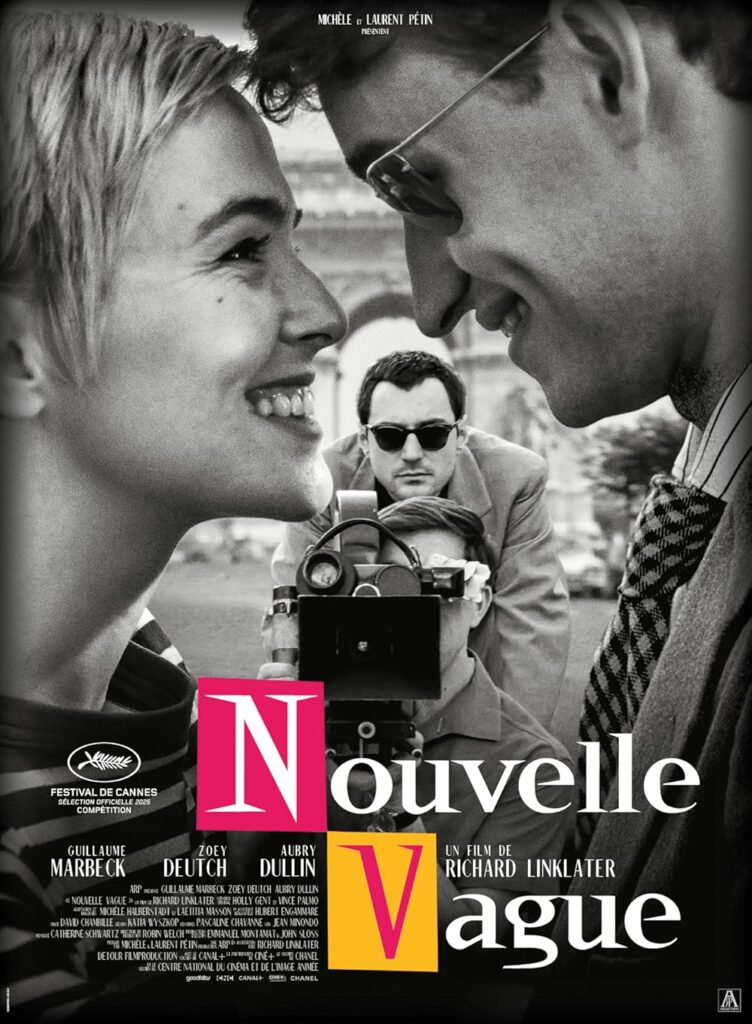

Nouvelle Vague

Introduction

In many ways, Richard Linklater’s Nouvelle Vague can be a contrasting companion piece to Richard Linklater’s Blue Moon (2025). Both films essentially tell you contrasting tales of artists at different junctures in their lives. While Lorenz Hart (Ethan Hawke in Blue Moon) was at his fag end of his career, driven by guilt and desperation, you are introduced to Jean-Luc Godard (Guillaume Marbeck) early on in the film wherein he is shown to be watching a film as a film critic. And while we witness accolades pouring in for the filmmaker after the film, Godard remains firm on his stance of how he completely disliked the film. So oddly, this becomes a driving force for him to tell stories (after witnessing Truffaut’s film The 400 Blows) in a revolutionary phase for French cinema popularly being referred to as French New Wave that saw as many as 162 ‘New’ filmmakers making their filmmaking debuts while influencing thousands of cinephiles and future filmmakers from over the years. But in the heart of hearts, the drama here remains a charming love letter to the histrionics of filmmaking, even as Richard Linklater provides a tribute to perhaps one of his favaourite filmmakers of all times – Jean-Luc Godard.

Story & Screenplay

Written by Holy Grant, Michele Petin, Laetitia Masson and Vincent Palmo Jr, Nouvelle Vague almost forms a subtext of its own of denoting a fight against an establishment – except that this fight isn’t against the government but established French filmmakers who were very compartmentalized in their approach towards cinema. From Godard’s POV, the thinking was simple – innovate and create cinema that offers freshness to the viewers, without necessarily worrying about the accolades. This is represented through two iconic lines that are uttered at different junctures in the screenplay – ‘Art Is Never Finished, Only Abandoned’, and ‘All You Need For A Movie Is A Girl And A Gun’. But what remains unspoken are the breakthrough techniques employed by Godard while making his debut feature Breathless (1960).

Studying Godard and his creative choices immediately transported me to the world of Anurag Kashyap and the kind of process that he employs in making a film – having a strong influence of Godard. Be it selecting a rank newcomer in the form of Jean-Paul Belmondo (Aubry Dullin) – someone who has just finished military service, or utilizing the services of the Hollywood star Jean Seberg (Zoey Deutch) while demanding her to surrender to the process of his filmmaking style. It is important to note that the deft bouts of comedy erupt from moments creating on set, wherein you are literally a fly on the wall while witnessing the script being deliberately finalized on set to ensure artist spontaneity, or simply using innovative ‘shaky’ camera techniques in what we understand as a guerilla style of filmshoot.

It is interesting on how to an onlooker, the camera angles might seem to be odd – often placed on a building or a fitted inside a moveable trolley (something that we now know as the trolley shot), all but to add the cutting edge of the time. Even the aspect ratio employed is 4:3 (1.37:1) which we now know as Academy ratio. As an avid cinephile and a student of cinema, I was in awe of the world created here even while being witness to the leisurely filmmaking technique being criticized by the jittery producer Georges de Beauregard (Bruno Dreyfurst). This, while the same being met by diverse reactions from Jean-Paul who remains playful with it, or a moderately insecure Seberg who questions Godard’s style while contemplating on leaving the film. I could totally imagine the cultural shock of the cast and crew of an Anurag Kashyap film who would often be unaware of the ‘confused’ film being made, until the final product is ‘absolute cinema’.

If you were to ask me on the places I would love transport myself to, then my answer would be either a theatre or a film set. But the film set may not necessarily be indoors – something that you are witness to, early on in Godard’s career with his insistence to shoot in real-time on real-locations where all the world is a film set. By that logic, normal people become extras even whilst not really having to worry about continuity in words of Godard who goes onto say that continuity often interferes with the essence of a scene. If you are too focused on the continuity, you lose a grip on the organic approach employed thereby ruining the film. If only modern filmmakers were to take this piece of advice without worrying about validation from some silly ‘elitist’ youtubers (there, I said it…we all know the ‘cartels’ in town).

One little criticism for me with respect to the screenplay was in the final act that showcased the post-production of Breathless (1960). For me, the portion felt a little too abrupt and a tad too fleeting for me to be informed about the creative choice of Godard. It was the one little spot in an otherwise speck-free drama that made me fall in love with cinema and its craft all over again. And oddly to the people in the midst of the shoot of Breathless, they were invariably witness to greatness which would only be appreciated in hindsight. Much like Godard too who just wanted to make ‘his’ film without worrying about the outcome. Creativity prospers with innovations, not with formula! And the outro captions further establish this fact!

Dialogues, Music & Direction

The dialogues might seem to be conversational here, but the situations created allow humour to cut through the scenes with respect to the lines too. This, even whilst maintaining the profound relevance of cinema with lines like “We believe films shouldn’t cost much. It’s the way to creative freedom”.The BGM uses the rawness of the surroundings to transport you to the late 1950s, specifically in the midst of a shoot transpiring in a neighbourhood in Paris. The cinematography tries to replicate frames from Godard’s filmography but a distinct difference remains in allowing the frames to be still, as opposed to the shaky frames employed by Godard. That said, the monochrome adds texture to the framing often elevated by the classic Academy Ratio that instantly gives you a feel of the older classics.

The editing pattern is deliberately choppy, often replicating the chaos transpiring on the shoot of Breathless. Director Richard Linklater provides rich tributes to his favourite filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard by creating a world that stays true to the title of the film. Underdog is a word often used for the characters, and whilst the protagonist is an underdog himself, so is the world created here – and that automatically adds texture to the proceedings. The implementation of a film about a film is an instant hit with my sensibilities too, and I was witness to the craft of Linklater in creating bouts of deft humour along the way while allowing me to be a fly on the wall. The direction is superb here.

Performances

The performances are wonderful to witness by the members of the cast. Antoine Besson as Claude Chabrol and Adrien Rouyard as Francois Truffaut maintain such impeccable postures in convincing you about the real personalities of the iconic filmmakers in question. Paolo Luka Noe as Francois Moreuil has his moments to shine. Pauline Belle as Suzon Faye and Matthieu Penchinat as Raoul Coutard subtly contribute to the situational humour in the drama, rather effectively. Benjamin Clery as Pierre Rissient and Bruno Dreyfurst as Georges de Beauregard are important cogs in the screenplay, and both of them manage to impress here.

Aubry Dullin as Jean-Paul Belmondo has a playful charm to his character that he wonderfully exploits here. Zoey Deutch as Jean Seberg showcases her vulnerability with deft glances and utmost grace, while forming a solid balance between her playfulness and insecurity (given the lack of lines provided to her character in Breathless). Guillaume Marbeck as Jean-Luc Godard is brooding with his body language and demeanor while fully committing to this virtue through his mannerisms. He is understated but always vigilant with his filmmaking, two deftly contrasting virtues that are well conveyed through his performance. He was a treat to witness here despite the ‘pressure’ of depicting an iconic director who is an all-timer!

Conclusion

Nouvelle Vague is a charming little love letter to French New Wave featuring legendary director Jean-Luc Godard’s histrionics of filmmaking, something that makes for a brilliant watch. This, while the drama is a contrasting companion piece to Richard Linklater’s Blue Moon (2025). As they say, the artist passes away, but their art is always immortalized. And yes, ‘cinema about cinema’ is still my favourite genre! Highly Recommended!