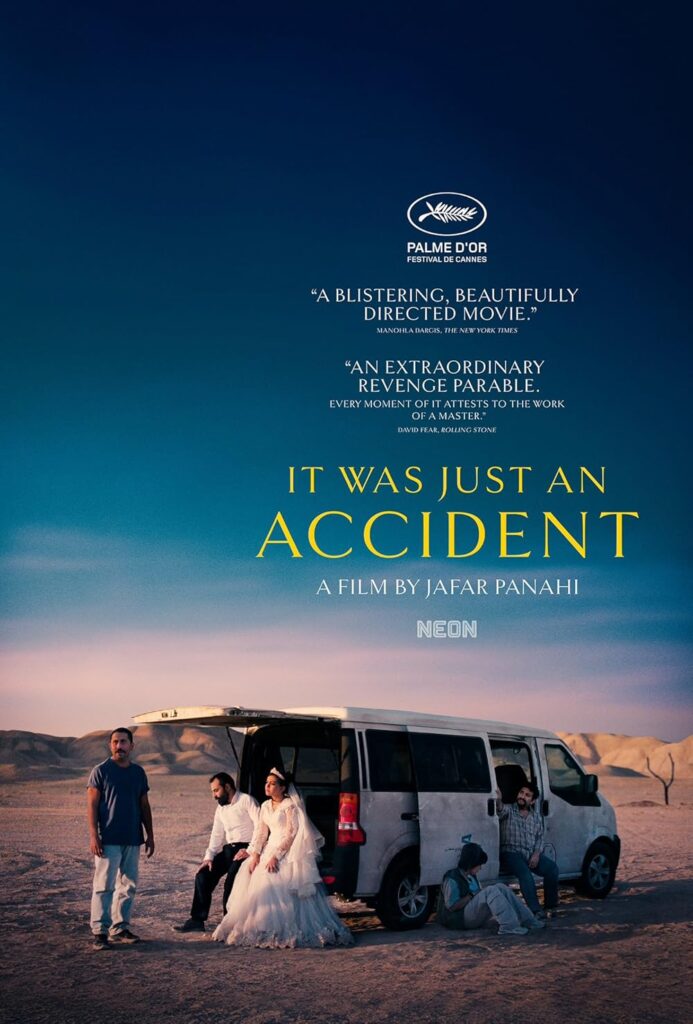

It Was Just An Accident

Introduction

The subtext of the Iranian film It Was Just An Accident, France’s Official Submission to the Oscars of 2026, is hidden in its title – something that is presented as a metaphor in its opening act. You are introduced to a man casually driving in the dark with his family by his side. The mood is upbeat even with a hint of the political regime sprinkled in a fleeting moment when the man doesn’t wish to play ‘loud music’ at the behest of his daughter. Soon, tragedy strikes when the man runs over a dog – another fleeting incident in context to the story but an important one. The parallels that its maker Jafar Panahi wishes to explore is of the street people who are casually bumped off from the roads by the current political regime of the Iranian Government, a trait that can easily be extended to some of the other countries too. In the same moment, the man’s daughter is told by her mother on how the incident wasn’t her father’s fault but it was due to the lack of street-lights, implying on how it was God’s wish. This ‘killing’ in the name of God finds its reference again in a separate scene wherein a character equates the ideology to the terrorist organization ISIS.

Story & Screenplay

Written by Jafar Panahi, you can almost make out that the seed of the story for It Was Just An Accident is coming from a personal space in the veteran filmmaker’s life when he was imprisoned in 2010 by the Iranian regime. Hence, the representation of himself extends to a bunch of oddballs who seemingly come together with the purpose of identifying their perpetrator who had tormented them in jail. The underlying theme remains that of revenge, but the same sentiment is deeply layered and stemming from a space of angst given the torture endured by the individuals. In a way, it remains a silent resilience that takes the form of revenge while identifying specific traits of the tormentor – similar to how a whiff of perfume could transport you to your past in a completely different context.

The POV shift takes place right after the cold open wherein you are introduced to Vahid (Vahid Mobasseri), an Azerbaijani auto mechanic who remains a silent spectator while witnessing the squeaking prospethic leg of the man from the cold open, immediately transporting him to a man named Eghbal aka Peg Legs, his chief tormentor from his prison days. The fleeting moment turns into an impulsive one, prompting Vahid to not only chase the man but later kidnap him and (almost) bury him alive until doubts creep up. His sentiment is a raging metaphor for the simmering anger of the common people who are forever suppressed under the authoritarian regime in place. In other words, people like Vahid represent the dogs on the street who are captured in the name of God while leaving their fate to God too.

It is interesting on how the events play out like a black comedy as opposed to a full blown thriller, even as you are introduced to the fleeting clan of Vahid – a photographer, a couple engaged and soon-to-be married, a casual guy, all joining forces to identify their perpetrator. It is an extension of the mental scars that have forever been fresh, even as a raging bout of revenge is what ties the characters together. They remain a bunch of corporate employees who would team up to overpower their boss in another world, even while their juvenile antics would account fir subtle bouts of humour. And yet, it must be commended on how well the tone of the drama is maintained, in the eye of a thriller while never losing sight of the broader political commentary in place.

What sets these character different from Eghbal is on how hesitant they are in punishing a man without being sure of his identity. In a sharp contrast, Eghbal knew none of them personally, but still was the source of pain and suffering that the group had had to endure. This streak of humanity is extended in a latter scene wherein Vahid opts to help the pregnant wife of the man while willing to take care of their daughter during the passage of child birth. For a fleeting moment, it separates the streak of revenge from that of humanity through the character of Vahid.

You get a glimpse of the controlling nature of the regime through many of the fleeting moments in the film – a scared character wishes to bribe another character (thinking he is a part of the regime) with the intention of getting his marriage photos being clicked seamlessly. Or in another instance wherein a heavily pregnant character isn’t immediately attended just because her husband wasn’t accompanying her. The regressive nature of the regime forms a means of survival for two sets of people – one who quietly follow its fixed set of rules like Eghbal, and the other who are suppressed and tormented like Vahid.

Interestingly, the 14 minute single shot sequence at the end, forms the basis of this argument – from anti-government ‘propaganda’ activists being jailed to labourers joining them just because they asked for a hike, even while the reason being provided is that the concerned person was just doing his job for his family. The convenience of the reasoning is the exact reason why it will irk you all the more, and if I were to pause and look around – the situation ain’t too different ‘elsewhere’ too.

This brings me to one of the greatest endings that I may have witnessed in a very long time – a sequence so devastating that it had me thinking about Vahid long after the film had ended. The psychological edge created was so immense and so brutal, that it had the power to not only transport you to the psyche of Vahid while being tormented in jail, but also allowing you space to experience his fear when he witnesses the squeaky sound of the prosthetic leg again. And for Vahid, his future would continue to remain uncertain – no matter how good he wished to be while helping the family of Eghbal, much like most folks silently being suppressed in an authoritarian rule (at times that is projected as a democracy too). Or can you expect a happier ending for Vahid with the same setting, signalling a sense of hope? Maybe, maybe not! And therein lay the genius of Panahi the filmmaker – the same setting giving you no answers but two distinct possibilities.

Dialogues, Music & Direction

The dialogues hold a subtext of pain and rage while often driving the sentiments of most characters here. The BGM comprises of raw ‘natural’ sounds that immediately create an immersive experience here, instantly drawing you in the narrative.

The cinematography by Amin Jafari remains the interesting part here, particularly given how Panahi did shoot this film without permissions from the authorities. And you see that in this guerilla style of filmmaking that is now a forte for Panahi. From the discreet shots inside the car to far-out zoom-in lenses capturing some action on the streets, the frames add to the raw ambience of the drama. Also, Panahi isn’t interested in concealing the identity of the perpetrator, using a red hue to convey his true visceral identity, a technique used at the end too in a wonderful 14 minute still-shot. This, while even using his frames to depict various prisons – be it the toolkit in the van, or the van itself, or the never-ending landscape of the desert – all the world is a jail in an authoritarian regime.

The editing pattern is leisurely – allowing drama to simmer without infusing too many jump cuts. This included a 14 minute single take at the end that went on like an unfiltered and raw footage of torment when the tables turn. But there are two jump cuts incorporated with precision – one at the start and the other at the end, something done deliberately to seamlessly switch the tone of the drama.

Director Jafar Panahi is an absolute legend, often utilizing cinema as a tool to highlight the flaws of the regime and criticize the government. This is drastically different from filmmakers from other countries who are nothing but mouth pieces of the authorities. And for Panahi, this does come (probably) from a very personal space, given how there is a sentiment of rage associated with the drama along with hints of hopelessness. This reflects in his world building and characterization too, both of which are sprinkled with a devastating political subtext. There is craft in the way Panahi constructs the drama while delving deeper into the psyche of his characters. This brilliant piece of direction needs to be savoured and studied for the impact it delivers.

Performances

The performances are wonderful by the members of the cast. Afssaneh Najmabadi as Eghbal’s wife and Delnaz Najafi as Eghbal’s daughter have their moments to shine, particularly the latter who conveys emotions rather seamlessly. Mohammed Ali Elyasmehr as Hamid uses his expressions to convey his rage in the form of an aggressive streak rather effortlessly. In a sharp contrast, Majid Panahi as Ali is understated and restrained while giving a different dimension to the group. Hadis Pakbatten as Goli is first rate even while maintaining a fine balance between a black comedy and the angst that are reflective through her mannerisms and body language.

Mariam Afshari as Shiva is calm and calculative even while holding on to all the pain and scarred emotions within her. The only time she lets them out is in the climactic scene that is gut-wrenching, even as Mariam manages to impress here. Ebrahim Azazi as Eghbal is terrific in a character that will play with the psyche of the viewers. There is a cold entity buried deep inside him without an iota of remorse that often comes out in the form of fear of his identity being revealed (you see his daughter complaining about no one comes to their home including neighbours, something that can be equated to this trait of Eghbal). And he is brilliant as ever here.

Vahid Mobasseri as Vahid is understated by often oscillating between rage and forgiveness. It is almost as if he has been brought up on the principle of the latter but given his torturous period in a prison, the seeds of the former are in play too. He beautifully encapsulates the spirit of the labour-class with his body language and expressions while accounting for so many emotions along the way. This remains a quietly powerful act that will engulf you and stay with you long after the film has ended.

Conclusion

France’s Official Submission to the Oscars of 2026 (in the Top 15 and a frontrunner in the International Feature category), It Was Just An Accident is the devastating state of authoritarian affairs veiled in an engaging thriller with deep political undertones that makes for a brilliantly impactful watch. And for all budding filmmakers out there – THAT IS HOW YOU END A FILM! Highly Highly Recommended!